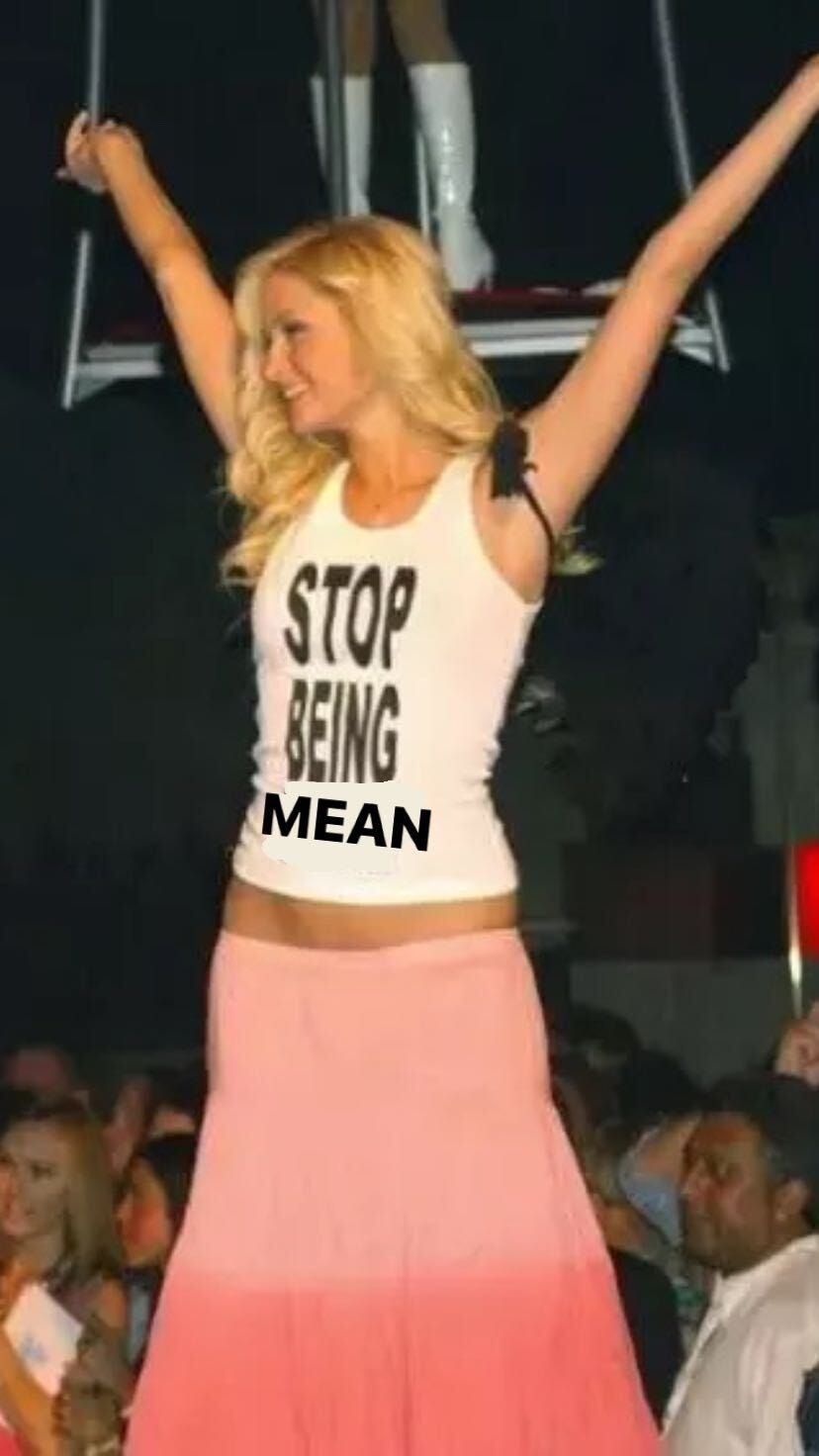

Being mean online is the same as being mean IRL

The pandemic erased the line between “bad online, normal IRL.”

Over the years, I've been reassured numerous times that someone in my industry who I think is an asshole online is “actually really nice IRL.”

Being a dick online is not new. You’re separated from your own actions by either a cloak of anonymity or freedom from looking someone in the eye when you snarl back some cutting response to their take. I think it pleases the same part of our brain that makes us remove the ladder from the pool where our Sim is swimming. When we’re offered a consequence-free way to explore our worst curiosities, we take it. But being a dick online is no longer consequence-free.

I realized this recently when someone who had been rude to my friend on Twitter one (1) time three (3) years ago came up in conversation (holding a grudge like this is my own persistent flaw). I relayed my general perception that this person seemed unnecessarily aggressive online, and many people attested that, IRL, this person was perfectly lovely. Rather than placate me, as this would have a few years ago, this only made me more frustrated.

After two years of online interaction being the primary way of socializing, hearing that someone is nice when they’re not on Twitter feels as reasonable as someone being like, “They’re actually really nice when they’re not in the living room.” The pandemic has erased any line that stood between our online and offline selves. If you’re mean online, you’re now basically mean in real life.

Reflecting back on my own Twitter use, I’m not innocent, either. While I don’t think I’ve ever gone out of my way to take issue with someone else’s tweet (too stressful, just shit-talk it in your group chat like a normal person), I’m more flippant and skeptical about things than I would be were I saying them in front over over 6,000 actual real people. There are people whose feelings I’d hurt if they ended up reading the things I’d snarked about for close to no reason, other than to score points in the internet’s overall game of “the meaner you are, the smarter you appear.”

Which is why I don’t necessarily blame anyone for uncharitable online behavior. Through likes and follows and other engagement, they’ve been rewarded for it over and over again. And up until now, there was a separation of church and state that allowed them and the people around them to compartmentalize that behavior into a category that had no bearing on real life. But more rapidly than anyone could have predicted, the tables turned, and already I’ve noticed the reverse: there are people I get along better with online than in person.

As we continue to stumble across ways the pandemic has forever altered our ways of thinking, this might be one of the more significant — especially as we hurdle towards whatever the metaverse is going to look like, and the increased blurring of lines between online and off.