I do not dream of AI slop

Stealthy AI images and videos are supplanting influencer content, drip-feeding viewers counterfeit aspiration and nostalgia.

Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, written by Kate Lindsay and edited by Nick Catucci.

Begging you all to just feel bad about your life the old-fashioned way: watching your peers with previously undisclosed wealth start buying real estate.—Kate

New on ICYMI: Kat Tenbarge joins us again, this time to break down the sneaky ways free speech was already being eroded online, long before the killing of Charlie Kirk.

Head over here to subscribe to ICYMI wherever you listen to podcasts 🫶

My time on Tumblr came and went, and early this year I deleted Twitter and Facebook, which means my longest-running social media relationship is now with Pinterest. If Tumblr introduced me to nu-folk music and progressive politics, then Pinterest is responsible for everything else about my personality. It inspired my love of cooking, sewing, knitting, and taking pictures of natural light hitting the corner of a room. I have, in many ways, brought a number of my Pinterest boards to life. Anyone being raised on Pinterest now may not be able to say the same.

“[AI] Slop is everywhere on Pinterest, frequently ranking in the top results for common searches,” Maggie Harrison Dupré wrote for Futurism back in February. “It persists across classic Pinterest categories like home inspiration and DIY hacks, fashion, beauty, food and recipes, art, architecture, and more—and often links back to AI-powered content farming sites that masquerade as helpful blogs, using Pinterest as a tool to draw in viewers to useless chum content just to cash in on lucrative display ads.”

Pinterest’s slop problem came up while my sister’s wedding party was getting our hair done a few weeks ago: When you search for “bridesmaid updos,” you now have to take extra care to make sure the picture you end up bringing in is, in fact, real.

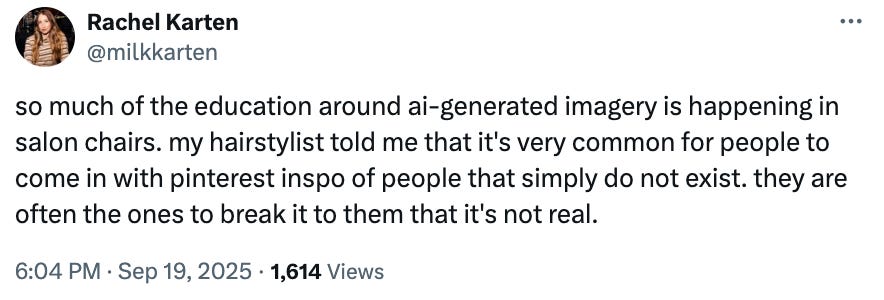

This is something Rachel Karten remarked on on Twitter:

When I made the brave and beautiful decision to get bangs earlier this month, I asked my hairdresser about her clients bringing in AI photos for inspiration. She specializes in color treating hair, and said it’s most challenging when a client brings in a photo of hair in a color that’s fundamentally impossible to achieve in real life. I’m no stranger to bringing a photo of a bony, bird-like French woman with a bob to the salon and wondering why I ended up leaving the chair still looking like, well, myself, but this kind of revelation is something else entirely.

There’s always been an element of unattainable aspiration online. The “Instagram vs. reality” trope was born out of an awareness that we all choose to curate and project our life in such a way that obscures any imperfections. Instagram is not real life, you hear people say.

Still, it could have been. That was what was so enticing about it. Everything on the screens was theoretically attainable, which is why the rise of Photoshop and airbrushing and filters on social media was, and still is, met with backlash and analyses “exposing” the influencers and celebrities who hacked twenty pounds off of themselves using the eraser tool and presented the image as fact. We feel duped. We reject the idea of being made to desire something counterfeit.

But while some of us are learning how to identify AI images based on “vibe” alone, we’re a long way from having the same keen skepticism we do when we see a warped fence behind an influencer’s thigh. We easily register these traces of editing that make the photos inconsistent with reality. But with an AI image, there’s no reality to compare against.

“Where’s the bedframe from?” the Pinterest comments ask. “Where’s the quilt from?” “Does anyone know the brand that made the coffee table?”

It’s not that the table or quilt is expensive or hard to source, as these things often are when a celebrity posts a house tour. It’s that there aren’t any answers at all. These things don’t exist.

Posting aspirational AI photos is annoying and lazy and disappointing. But I can’t help but also think about the about the dynamic it’s creating between us and our own reality when we are trained to see uncanny, machine-invented depictions of everything from our food to our homes as our North Stars, and what it will do to our brains to never be able to achieve them. What would I be now if that “everything else” about me was fake?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Embedded to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.