It’s too easy to delete things

Our digital lives are getting more precarious, not less.

Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, written by Kate Lindsay and edited by Nick Catucci.

“I’m gonna commit a homicide, and I’m gonna enjoy it.”

It’s an incredible TikTok lede, and by the time you reach the end of @gi11withag’s aka Gillian’s video, you’ll feel the same way. To stop her Mac from overheating every time she plays The Sims, Gillian got herself an external hard drive and spent nine hours moving over every single game file and expansion pack. She also attempted to transfer some files she had on her brother’s computer, but because he was annoyed at her interrupting him to do this, when it was complete, he yanked out the cable instead of ejecting the hard drive.

“I plugged it in and guess what: All of my files were corrupted,” Gillian says through tears. Not only had this ruined her entire game history, it also destroyed two years of college homework assignments and four years of photos she was also trying to move.

“Four years—gone,” she says. “Because he was like, ‘Whatever, it’ll be fine.’”

I remember being nine years old and losing access to almost all of my progress on a Pokémon game when my Game Boy crashed and died on the Eurostar. I threw an absolute tantrum that my parents had no patience for, but now that I’m in my 30s I can (brag) better articulate the issue: It wasn’t just the loss of the game, but the sense of betrayal that something I put so much time and effort into could be taken away from me through no fault of my own.

This problem is exclusively digital. Outside of a nuclear bomb dropping, there’s not a single IRL event that could erase years of a human’s possessions and existence in just one second, without any time to intervene and salvage the loss. And a nuclear bomb is not something your average brother has access to. What’s wild is this kind of digital fragility is not a hallmark of our early internet days, but something that has, if anything, gotten worse.

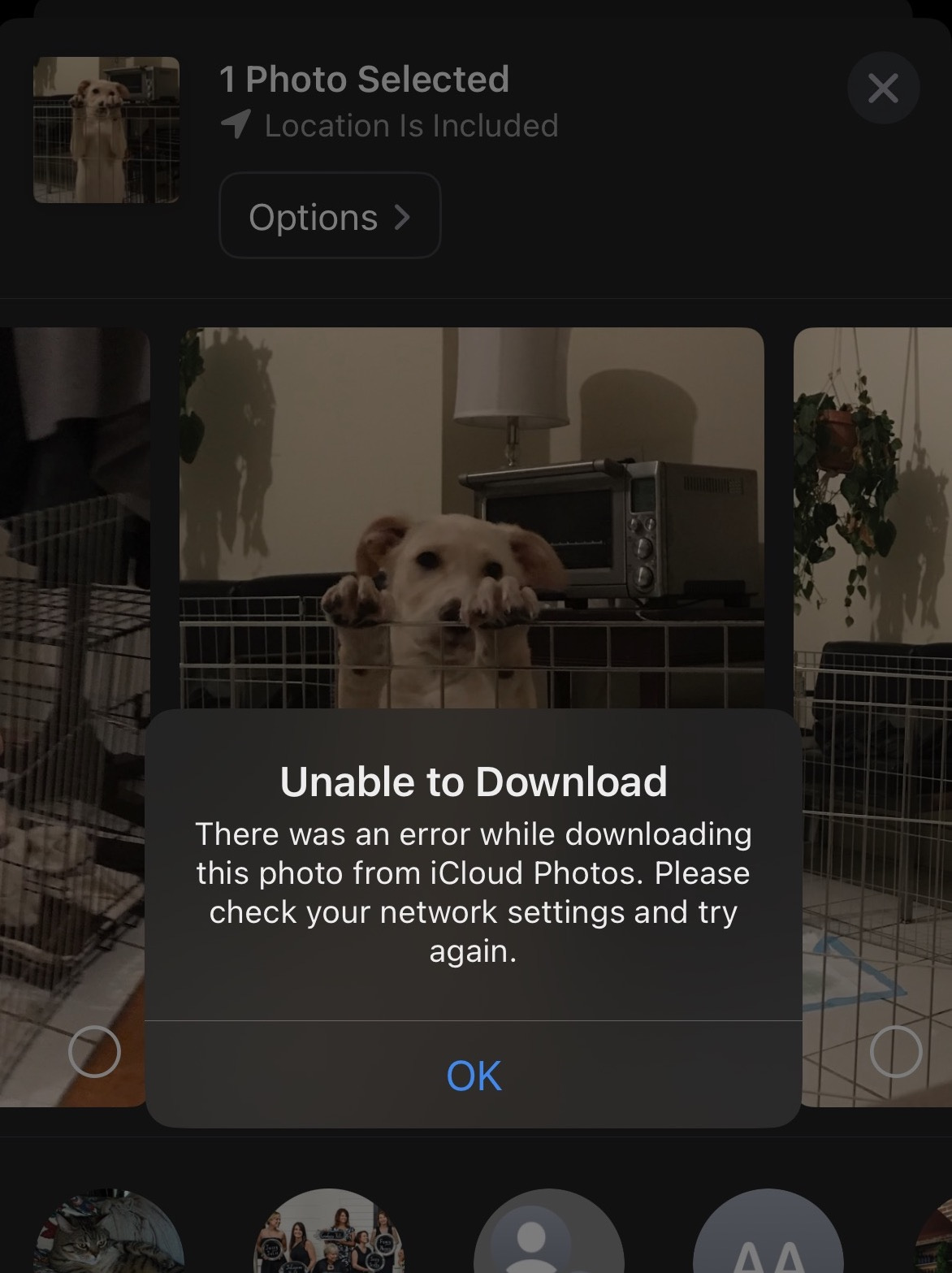

It would be one thing if all that was needed to protect our digital lives was to follow the instructions of a single hard drive, but these days it’s impossible to anticipate all the ways our digital lives could be put in jeopardy. It’s like plugging the holes in a sinking ship—except as soon as you fix a leak, something totally unrelated catches on fire. Literally as I was writing this, my group chat was sharing puppy photos of our respective dogs when my friend Rachel was hit with this:

No reason. No explanation. Just: You can’t access these memories anymore, and we have no information about what you could have done to prevent this.

In a recent interview with The Fence, author Dolly Alderton replied to a question about how she was doing by launching into this: “Stressed out because I just cannot operate my iPhone, and there’s been a massive drama with the iPhone iCloud backups and I just cannot believe that my entire life has become dependent on this one device and I feel like I’m in a toxic co-dependent relationship with it that I never agreed to.”

Whenever I’m doing important interviews for work, I record on two devices in case something goes wrong. But the average person should not be expected to live with prepper-level paranoia at all times, not least because it’s impossible to know where to start or end. It reminds me of an interview I did for The Atlantic with writer Ashley Reese, whose husband, Robert Stengel, passed away in 2022.

Websites shut down, accounts get hacked, devices break. It’s not safe to assume that direct-message conversations and other social-media memories will be there forever. “My current plan is to just try to do as many digital copies of things as possible,” Reese told me. She has 10 years’ worth of messages with Stengel, and plans to back them up on her computer, in Google Drive, and to her iCloud. “I would be absolutely devastated if I lost that stuff.”

You can buy and download, say, a TV show a streaming service has randomly decided to remove. You can duplicate and save it, along with other important files, onto a hard drive. You could, I guess, do the same thing on another hard drive in case one of them gets corrupted. But that is a lot of time and money to insure against a loss that the very infrastructure of our digital lives is premised upon not happening. While physical photos and DVDs and other bygone tech may be slow and clumsy, at least you can put them somewhere that brothers can’t reach.

Great and sad piece. Short of nuclear bombings other analog wipeout moments include flood and fire which often move too fast for people to grab their memories. Mostly this piece took me back to 2007 when I lost my full computer life and priceless memories of my mother. I found the old blog post. Bonus old school internet moment: this post was front paged on digg.com RIP https://www.baratunde.com/blog/2007/9/7/please-backup-your-hard-drive-now-twice.html

I'm a librarian and I'm constantly telling people to use automatic backup - in at least two locations. One can be Amazon but the other one needs to be not Amazon because even AWS has data loss.