Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, written by Kate Lindsay and edited by Nick Catucci.

Surprise! I’m the new co-host of ICYMI, Slate’s internet culture podcast. I’m joining Candice Lim every Wednesday and Saturday to expand on many of the same things I’ve been delivering to your inbox these past nearly four (!) years. Embedded isn’t going anywhere. If anything, this means I get to focus even more closely on internet culture and keep bringing you my favorite stories (and rants). You can listen to my first episode below, which is a proper get-to-know-me, and subscribe wherever to keep up to date!

—Kate

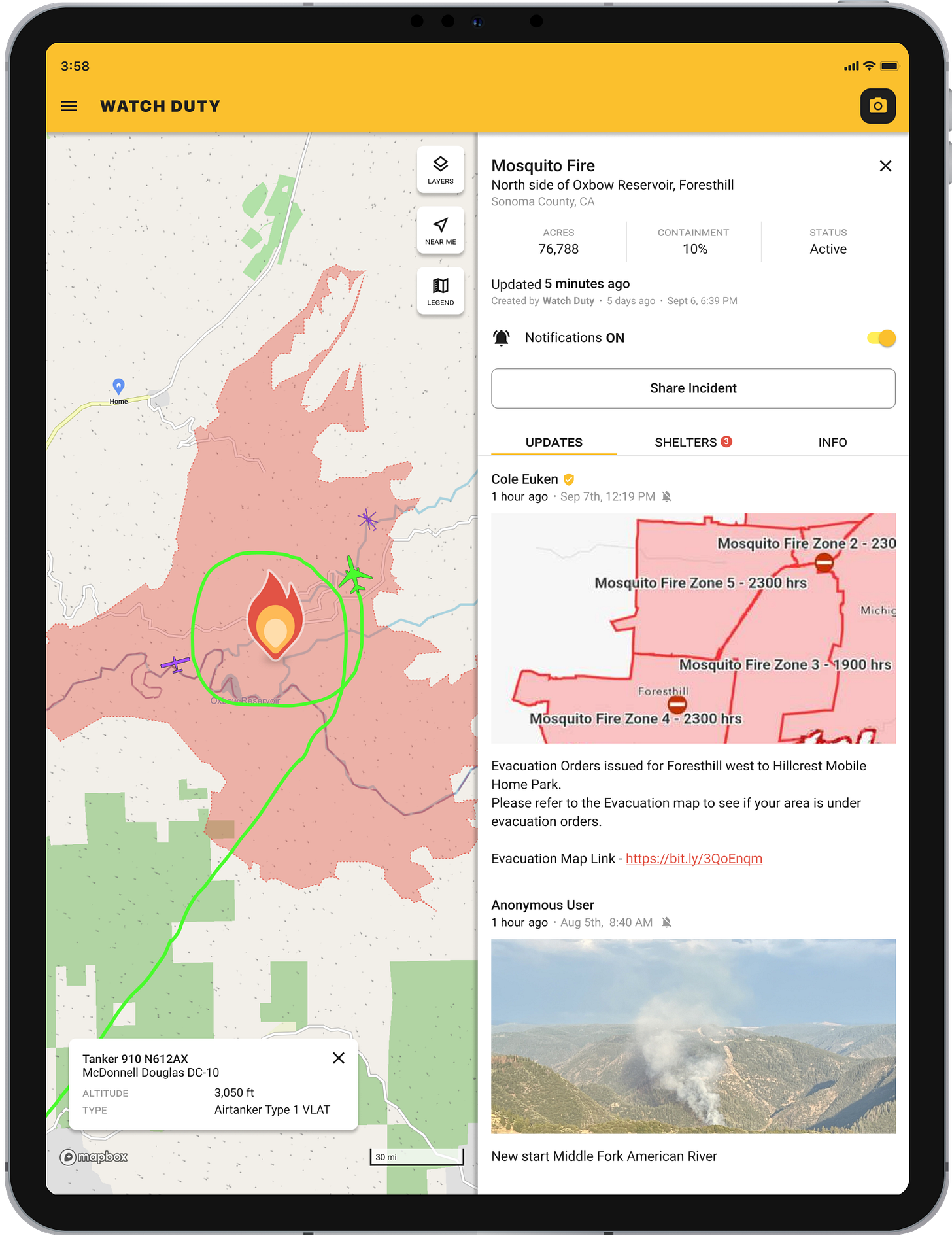

As wildfires engulfed the Los Angeles area this past week, many people across Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok focused on how to help. They were sharing updates, recommendations, and pulling together Google Sheets of places in Los Angeles where one could donate supplies, shelter pets, or get access to electricity. There was one app that appeared in almost every single recommendation: Watch Duty.

The public safety nonprofit’s app has shot to the top of the download charts thanks to its real-time verified updates on where the fires have spread, how the winds are moving, and whether or not you should evacuate. “Please tell them thank you from me,” my friend Hannah, who lives in LA, texted after I shared that I would be interviewing Nick Russell, VP of operations for the app. “Literal life-saver. Everyone I know has it downloaded.”

Here Nick and I chat about how Watch Duty was formed, the people whose lives have been saved thanks to the alerts, and what disasters they hope to tackle next.

How did Watch Duty start?

The real crux of creating Watch Duty came from our co-founder and CEO John Clarke Mills. He had a rich history in tech. He's created many software companies and sold them. After he sold his last company, he moved to a rural area in northern Sonoma County here in northern California and about six months after he moved in, he had several experiences with firefighting, helicopters flying over his home and seeing smoke, and finding challenges with getting information in any sort of timely manner and trying to piecemeal everything together. So with his background in tech he said, “There's gotta be a better way to do this.” He spent the rest of that year riding around on engines, learning more about wildland fire response and suppression. And then in August of 2021, [Watch Duty was] born in the original three counties, and the focus was to get communities real time, actionable information about events occurring around them.

Our second year we moved to cover the entire state of California and at that time, we got towards the end of fire season and we started hearing regularly from first responders, tanker pilots, firefighters, and engines who were utilizing Watch Duty. So we started asking questions like, Why are you guys using Watch Duty? You have all this stuff. And they just started laughing and saying, like, No, we don't. We don't know what's going on off on the other side of our county, we don't know what's going on out of town, but we're expected to respond to those incidents should the need arise. And so the way that they were leveraging Watch Duty, much like communities, was to maintain situational awareness, just in a different arena.

So we started learning more from them and then started asking, How can we help? You guys are faced with all these problems, you're hitting red tape after red tape of budget constraints. They gave us a lot of things that would be helpful for them in the app. Some of those translated to features for the community, but many ended up in the Watch Duty Pro version which is specifically for first responders. The adoption was quite quick in our local area. In the past week we've increased our user base by 2 million users, bringing the total up to just over 5 million users.

The closest equivalent I can think of in New York is something like the Citizen app. Is this similar in the sense that it is community-reported?

We have a volunteer team of both contributors and reporters. In order to get on our team, we do a panel interview, we do a full background check, and then we bring this person on. They start as a contributor, and so what that means is they're kind of gathering local information, helping out with the areas that they're familiar with. Many times these folks are active and retired firefighters, first responders, or radio folks and so these are vetted reporters that are doing this with decades of experience. They know how to look at wildfire cameras and distinguish smoke from steam and dust, they can see an incident escalating on camera virtually without actually being there. And so that's probably the biggest thing that separates us from apps like Citizen, is that we're not crowdsourced. We certainly use crowd-sourced information as a signal to validate, but for us everything's about validating what's actually happening in real life. So there may be theatrical things on social media or the news media, and then we take that as a signal to go validate and determine what our response will be.

From the work you're doing, what can local governments or federal governments do better to stay on top of all this?

The biggest point I've been trying to push to them is not just issuing wireless emergency alerts or evacuation warnings and orders. People are hungry for that granular context. I don't want a police officer showing up at my door and telling me it's time to leave everything I know and love and worked so hard for without understanding why, but at the same time, that police officer can't stand at my front door and brief me on the entire situation and the danger that I'm in because his goal is life and safety. He needs to get to the next house. [This is] what I've tried to explain to these emergency managers—and don't get me wrong, I don't fault them at all. They really are blocked by so many constraints, the biggest one being [lack of] personnel.

Finding a balance and communication there is certainly step one, but it goes beyond just the cookie cutter emergency alert. By "cookie cutter" I mean the government has developed plans to respond to emergencies and create evacuation based off of preplanning, but what I always try to explain to people is my neighbor couldn't care less if its until the fire's one mile away. I need to know when it's five miles away because I got livestock to move. I have pets to deal with. I have children. And so many times my decision to evacuate is gonna come well before any government alert, and I think that same thing rings true for many people.

With this fire we've seen on social media and through our support inbox, many people made decisions to evacuate well before warnings and then watched their home burn on a Ring camera as that warning came out simultaneously. So I think we need to look at the approach on how we communicate with our communities in these situations. Communicating early and often and not fatiguing people with wireless emergency alerts. I've seen a very large shift in 2024 and now into 2025 where agencies are heavily using the WEA (Wireless Emergency Alert) system and that concerns me, because when you start fatiguing people with that horrible emergency alert noise they're gonna start looking for avenues to turn that off. That's one of our biggest concerns at Watch Duty. The last thing we want people to do is silence our notifications and alerts.

How much do you hear from users in terms of their experience using Watch Duty, and I assume also their gratitude for this information?

I would say that every single fire that we cover where there is destruction in the residential properties, we receive at least one story of how Watch Duty allowed them time to gather their personal possessions or get out of harm's way. So specifically in this fire, we have received a plethora of support tickets from not only a local residents but people who maybe lived in the San Francisco Bay Area and had Watch Duty notifications turned on for LA because there's a loved one there, and they actually made contact with these people and said, "Hey, your house is in harm's way." I can't even count how many support tickets we have gotten that say that and the person that they were calling had no idea that they were under an evacuation warning or order.

How much does Watch Duty learn from each event, and how is the service positioning itself for the future?

We launch what's called our rapid response plan, which ends with the after-action review, and always has takeaways where we can improve. The theme always is how can we get people concise information quicker and our response time continues to cut down more and more. Our first post on this Palisades fire was four minutes after ignition. We always wanna tighten that up, and then on the engineering side on the back end, it's always developing deeper integrations with our county partners and emergency partners to get that information as fast as possible. We started out with wildfires. It's been our core competency and we focused on it, but we also understand that there are many other disasters that experience the same issues in communication and delays, and so we know that we can be of service there. The first thing that we're looking at stepping into is weather-related events, specifically river flooding. We didn't put fire in the name. It's called Watch Duty because the intention is we have a group of dedicated individuals that are watching 24/7 and fire, again, is where we started, but not where we'll end. We're not even close to done.

Welcome to the new weekly scroll, a roundup of articles, links, and other thoughts from being on the internet this week! Ahead, some good stories on flaking and loneliness, my proud contribution to the words of the year, and the media outlet that instructed employees to work harder to “offset” the death of their colleague.

What I’m consuming…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Embedded to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.