My Internet: Jaime Brooks

The musician and writer thinks Web3 has already made the internet worse.

Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, by Kate Lindsay and Nick Catucci.

Every week, we quiz a “very online” person for their essential guide to what’s good on the internet.

Today we welcome Jaime Brooks, whose band Elite Gymnastics has a new album, Snow Flakes 2022, that will soon be available on Bandcamp. She also writes a blog about the music industry, Streaming Services, for The New Inquiry. You can support her work on Patreon.

Jaime once performed a Taylor Swift cover that inspired a Guardian opinion piece, discovered the most beautiful voice she’s ever heard in a YouTube video with 76 views, and calls Web3 startup workers foot soldiers for the most swagless empire in all of human history. —Nick

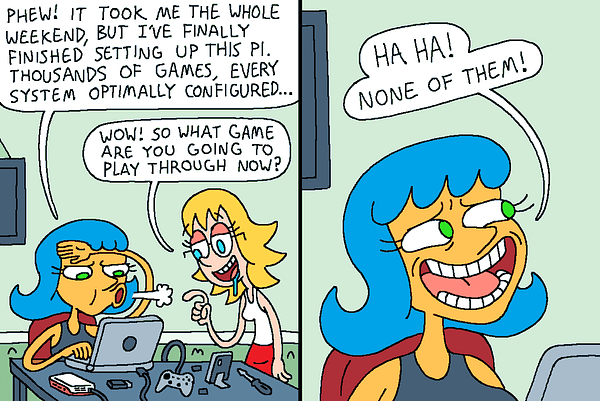

EMBEDDED: What’s a recent meme or other post that made you laugh?

JAIME BROOKS: This comic:

EMBEDDED: What types of videos do you watch on YouTube?

JAIME BROOKS:

My primary area of interest is music, so my favorite thing to do is to type the name of a song I love into the search bar and scroll all the way down to the versions of it that have the smallest amount of views. This is from a channel called Kevin Steel Guitar. Sometimes, in the comments, he will mention that he has been playing for 40 years. You can tell he just loves to play, and there is such joy and life in his playing. Maybe it’s just that it reminds me of the people I grew up around, but I find it really moving.

This appears to be from a karaoke night in a dive bar about an hour and a half north of Nashville. I found it while I was looking for cover versions of “I Was Country When Country Wasn’t Cool” by Barbara Mandrell. The singer has like, the most beautiful voice I’ve ever heard in my life, and she isn’t even trying to sound good. She’s clearly distracted and might even be on the clock working at the bar when this performance happens. As a country music fan, it feels like that video of Biggie freestyling on the sidewalk when he was still a kid. It’s like, a document of where this music comes from and what it’s supposed to feel like.

EMBEDDED: What do you use Instagram for?

JAIME BROOKS: I used to live with someone who had a big IG presence, and the risk/reward calculations inherent in every post were a regular source of stress. I would talk about how easy it is to determine where a photo was taken by studying background details and matching them up to Google Maps images, but people weren’t conscious of that stuff as much back then. I often worried I was just being a paranoid buzzkill. In the end, though, some guy did eventually match up the background of an IG post with a satellite image of our backyard and showed up at the house one night banging on the windows. I was told he shouted the names of all the people he expected to find there, including mine and my dog’s. I had already moved out by then, but the damage had been done. If there was some other, more efficient way to watch Azealia Banks’s stories I doubt I’d ever even open the app.

EMBEDDED: Do you tweet? Why?

JAIME BROOKS: I just see it as a form of posting. I could probably write an entire book just about my experiences with and feelings about Twitter specifically, but the specific characteristics of the platform are ultimately unimportant. Nothing about Twitter is special except for the fact that it exists on the post-smartphone internet where posting is no longer a niche concern. It’s just the message board that was there to capture the influx of new people that mobile interfaces brought online. I was posting before Twitter and I’ll still be posting after it’s gone.

EMBEDDED: Have you ever had a post go viral? What was that experience like?

JAIME BROOKS: I have been around a long time, so I have experienced many different kinds of virality. I was in the “Cool New People” box on the front page of MySpace once. I was on Tumblr for a few years in the early 2010s and my posts went viral in ways it’s kind of hard to fathom now. I posted a Taylor Swift cover and The Guardian posted an op-ed pondering the implications. I posted a long, rambling thread about problems in the music industry and music websites ran headlines about how everyone needs to check out my must-read Tumblr screed right away. The whole thing came to a head in 2013 when I posted a new EP on Bandcamp, which wasn’t being worked by a label or a publicist and wasn’t even available on streaming, the iTunes store, or as any kind of physical format. It included a song called “On Fraternity” that was about predators in underground music scenes, and everyone lost their minds about it. I was basically Music Twitter’s main character for a week, and an absolute deluge of opinions burst forth from all corners. The prevailing take was that I was “mansplaining” feminism, which was condescending and disrespectful to real women.

I wasn’t using words like “transgender” or “non-binary” to describe myself back then, because I hadn’t run into them often and didn’t fully understand what they meant. Music was the way I explored and expressed femininity, and that had been working out for me. At that point in my life I’d grown my hair out and I was starting to dress more feminine in public. People would write me to say I’d helped inspire their transition, which in turn helped to inspire mine. A bunch of careless media people decided this was controversial and tried to manufacture outrage to sell ads off it. They failed utterly. Nobody understood why they were supposed to care, and the end result is that they’ve all forgotten about it while I have to deal with the consequences of a Spin magazine roundtable discussion about whether or not I’m pretending to be feminist for clout appearing in my Google results for the rest of my life.

After that, I started experiencing a completely different type of virality. I was close to some music people who went on to blow up and become celebrities, which made me part of that world by proxy. That means even now, there are people following my every move online for no other reason than to dig for dirt on famous people I either haven’t met or haven’t spoken to in five years. Maybe the words I’m writing now will end up getting dissected by stans and CDAN readers in some musty subreddit somewhere, or maybe they won’t. Some days I wake up and notice a bunch of new people are following me because some random person I don’t know made a viral post about me that included enough celebrity namedrops or trending keywords to make the mere fact of my existence seem like breaking news. My life kind of feels like it’s littered with unexploded ordinance that could go off at any time. I’m so used to stepping over it every day that I think I kind of forget why I’m doing it. It feels a little overwhelming to think about. It’s hard enough to describe it. I guess I don’t get asked this question very much.

The science fiction writer Bruce Sterling gave a talk in 2014 called “Whatever Happens to Musicians Will Happen To Everybody” where he makes the case that musicians are always patient zero for new developments at the intersection of culture and technology. That our problems eventually become everyone’s problems. I think he’s right about that. Everyone else’s life is littered with unexploded ordinance, too.

EMBEDDED: Who’s the coolest person who follows you?

JAIME BROOKS: The first names that come to mind are Ayesha Siddiqi, Emmy Rākete, Andi McClure, Soleil Ho, Safy-Hallan Farah, and M Zavos.

EMBEDDED: Who’s someone more people should follow?

JAIME BROOKS: Naomi Elizabeth. Right now she mainly posts memes of herself, which readers of this newsletter may have seen around, but I know about her because of her music. I came across a video of hers in 2010 called “God Sent Me Here To Rock You” that popular culture still hasn’t caught up to. It’s over a decade old and everyone I show it to still assumes it’s brand new. Anything she does online is worth paying attention to. I also really like Alice Sparkly Kat, who writes about astrology. The director Lexi Alexander is a really good follow on Twitter, too. She’s just like, an extremely sincere person who could kill you with her bare hands. Keeps the timeline honest.

EMBEDDED: Which big celebrity has your favorite internet presence, and why?

JAIME BROOKS: Britney Spears is the only answer. She makes the internet feel like that movie Pleasantville where everything’s in black and white except for one person. An absolute legend of posting.

EMBEDDED: What’s one positive trend you see in media right now? What’s one negative trend?

JAIME BROOKS: Music media seemed to exist in a state of denial for a long time. Holdouts from the aughts just didn’t want to have to take internet culture seriously, and they’d often lash out if pressured to. Critics turning against MIA when she started putting glitched-out Blingee graphics in her album art and writing about Google sending our data to governments was a low point. Chuck Klosterman wrote a post for Grantland in 2012 about the indie artist Tune-Yards that was just about how baffled he was by her success, given that he wasn’t the target audience for it. He spent a good chunk of it imagining a hypothetical future where everyone that liked Tune-Yards feels embarrassed and confused about what they saw in it. A decade later, her original score for the film Sorry To Bother You is widely beloved in my circles and I’m not sure any of my non-media friends have any idea who Chuck Klosterman is. “I don’t want to have to care about this” was the party line on internet culture in music media back then, and it was the wrong position.

The positive trend I see is that this is changing! Cat Zhang’s internet scene reports for Pitchfork are fantastic, their “The Ones” column has been consistently strong for a very long time now and deeper dives like Alphonse Pierre’s recent piece on Jersey Club’s growing influence in hip-hop are even better. Marc Hogan’s reporting on Win Butler of Arcade Fire is one of the coolest things that site has ever done. I love how Lenika Cruz writes seriously and thoughtfully about K-Pop from her perspective as a BTS fan and an active participant in online fan communities. I love the newsletter No Bells, which reports passionately on internet micro-scenes that exist willfully apart from the ecosystem of prestige labels and PR that dominates coverage of indie music. It’s so thrilling to me to be able to read so much great writing about music by people who don’t feel like they’re above being online.

Read Cat Zhang’s My Internet

Read Alphonse Pierre’s My Internet

The negative trend I see in music media is that they’re too soft on crypto. Back in 2021, the populist backlash to the NFT boom on social media was incredibly swift and very well organized. People from fields like game development and animation worked tirelessly to summarize the anti-crypto argument in accessible Medium posts and video essays, and I think they were very successful in their efforts despite how well-funded the other side was. I would have liked to see musicians and music writers get more involved. I think that kind of passion and organization is what music desperately needs right now, and a lot of people missed an opportunity there.

I understand why it’s like this. There’s this newsletter called Water & Music that does data-driven analysis of the music industry. They did a post in 2021 about the live music industry’s total lack of a data-driven COVID strategy that was absolutely legendary. One of the most thrilling and resonant pieces about the music business I’ve seen in the past several years, on a subject that really warrants the attention. In a perfect world, cabinet-level positions in the executive branch would have been created for the authors to focus on that beat full-time. In the world we actually live in, Water & Music is now a DAO that reports exclusively on what’s happening at the intersection of music and NFTs. Nothing is happening there. Every time they post something new, I rush to go read it. Every time I do, it’s just a bunch of beautiful charts and graphs all communicating the same thing: there is nothing going on there.

Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, who have a podcast called Interdependence, earned a lot of goodwill by speaking out early and often against Spotify and the deleterious effect their business model is having on working musicians. I think they convinced a lot of writers and artists to start taking technology more seriously. Then, they came out of the closet as Ethereum stans and started insisting that the future of music was NFTs. I think the POV of early adopters like them was very overrepresented in early coverage of crypto incursions into music. I know of a lot of artists who took the bait and earnestly tried to make NFTs work for them, only to get blindsided by the backlash and the gas fees and the wash trading. I think skepticism should be a bigger part of the way music media reports on technology, especially when early adopters with existing crypto holdings stand to personally benefit so much from the impact they have on the narrative.

EMBEDDED: Do you subscribe to any Substacks or other independent newsletters? What are your favorites?

JAIME BROOKS: I like Ted Gioia’s The Honest Broker. It’s probably the most popular Substack about music? He’s this Jazz guy who sort of comes off like Ned Flanders if he got really into John Coltrane. He talks sometimes about having worked at McKinsey, and about having been some kind of “corporate fixer” in Shanghai in the nineties. I discovered him after writing a post for The New Inquiry about how the music industry is focused more on old music than new music and then seeing he had done a piece in The Atlantic shortly before called “Is Old Music Killing New Music?” My piece was based around leaked emails from the 2014 Sony hack, and his wondered why more people weren’t upset about the Grammys getting postponed. We were coming at the topic from very different directions, but the more I looked into his work the more I started to feel like we were arriving at similar conclusions. I appreciate his commitment to the art form, and his passion really animates the historical examples he uses to hammer points home. It’s a good read.

EMBEDDED: Are you into any podcasts right now? How and when do you usually listen?

JAIME BROOKS: Podcasts are so over. It was such a gold rush, and it couldn’t be clearer that nobody is ever going to strike it bigger than Joe Rogan did with the Spotify deal. What once looked like institutions of the medium are dropping like flies everywhere you look, fading unnervingly into the mists of memory with each passing day. Nobody’s heart is in it anymore. Some of those guys wake up every day literally praying that the Patreon numbers go down far enough to justify pulling the plug.

EMBEDDED: Are you playing any games right now?

JAIME BROOKS: Yeah, my partner is playing through Yakuza: Like A Dragon right now. The Yakuza series, which is called something else in Japan, is a long-running series focused on a particular neighborhood in Tokyo and the lives of working class people there over the years. The A-plot is usually a bombastic gangster narrative like you’d find in a Yakuza film, but the real meat of the series is the day-to-day minutiae of the people you meet along the way. It takes place in a really dense, walkable urban environment full of mixed-use development, and they’re full to the brim with stories that couldn’t exist anywhere else. The latest one, which doesn’t assume any knowledge of the previous games in the series, is a turn-based RPG about a charming, relentlessly upbeat protagonist who just finished a 19-year stint in prison. It can feel like a playable version of a TV series like The Wire or The Sopranos that mixes up crime fiction tropes with deep dives into a particular local culture. HBO’s High Maintenance and the Midnight Diner: Tokyo Stories series on Netflix are other good points of comparison.

EMBEDDED: What’s something you might want to do in the metaverse? What’s something you wouldn’t want to do?

JAIME BROOKS: I grew up around mostly truck drivers and mechanics. My early childhood was just like, a haze of greasy coveralls and gas station hot dogs and bathrooms my Mom didn’t want to let me use because there was always a crusty stack of Playboys in the corner. Later on in life, I went back to visit some of those people. An older couple who had long since closed down their garage and retired invited me warmly into their home, and we started chatting about old times. This was in 2009, I think. Midway through the conversation, we’re interrupted by a voice coming from a nearby computer. “Don’t mind that,” they said. “That’s just our guild.” I came to learn that this older couple were avid World of Warcraft players. They had formed a tight-knit friend group with a bunch of other older players from around the world, and they tended to leave a voice-chat application called Ventrilo running so they could chat with their guildmates all day long. They would all exchange gifts on holidays and keep each other appraised of the day-to-day details of their lives. It was like a bridge club, maybe. I got the sense that the in-game progression had long since become secondary to companionship in terms of what motivated them.

I have never encountered anyone who takes the idea of the metaverse seriously that knows more about the internet than the truck drivers and mechanics I grew up around. Technocrats keep trying to tell me my life is about to be completely changed by some shit my aunts and uncles have been doing for twenty years. People who did nothing but complain about how gross and off-putting gamer culture is for their entire adult lives get hired by a “Web3” startup and suddenly gamification is the solution to all the world’s problems. These people are all so unserious. At best, they’re wasting otherwise valuable talents on vanity projects to stroke VC ego. At worst, they’re willing foot soldiers for the most swagless empire in all of human history.

EMBEDDED: Do you think Web3 will mean a better internet?

JAIME BROOKS: It has already made the existing one worse. At this point, even if some blockchain product does ever achieve mass adoption, it will probably be because most of the people using it don’t realize it uses a blockchain. I don’t foresee any future where the “Web3” branding survives to see that day. Ten years from now, seeing it will feel exactly like seeing the phrase “Kony 2012” does today.

EMBEDDED: Do you text people voice notes? If not, how do you feel about getting them?

JAIME BROOKS: I don’t use them, but I have friends who prefer to communicate that way for various reasons. Generally, I am in favor of people making posts. Sending voice notes seems like posting. There’s this new app I’m interested in called Elis that’s like a social media app for posting audio clips. I use my ears a lot for work, so I haven’t had time to really sit down and try it out and see how it feels, but I like the premise.

EMBEDDED: What’s a playlist, song, album, or style of music you’ve listened to a lot lately?

JAIME BROOKS: My partner recently turned me onto this album called Beats and Breaks From The Flower Patch by an artist called Kitty Craft. It sounds like the missing link between Saint Etienne and the Avalanches, it came out in 1998, and that lady who made it is from Minneapolis. People who are familiar with my music will understand how delighted and I was to discover this record, but everyone else should check it out too.

EMBEDDED: Do you pay for a music streaming service, and if so, which one? When was the last time you bought a music download or vinyl record, CD, or tape?

JAIME BROOKS: I buy stuff on Bandcamp when I can afford to. I use my ears a lot for work, so I like being able to just buy a record when I notice it in a review or on Twitter and have it waiting in my collection for when I actually have time for it. I bought a cassette copy of an album called Love And Affection For Stupid Little Bitches by a band called Black Dresses, who are my friends. They included a really sweet note with the tape that they signed and drew pictures all over. In a fire, I would probably grab the note over the tape.

EMBEDDED: If you could only keep Netflix, Disney, HBO Max, or one other streaming service, which would it be, and why?

JAIME BROOKS: People should set up their own media servers and share access with their friends. Whatever money would have gone to the streaming services should go to the people maintaining the servers and the people who make the content that resides there to whatever extent that’s possible. The more that people understand the impact these platforms are having on culture, the less inclined they will be to pay for them. Whoever starts building alternatives now is going to be very popular in a few years.

EMBEDDED: What’s the most basic internet thing that you love?

JAIME BROOKS: I love to read posts. Sometimes I’ll actively seek out long threads on message boards or subreddits devoted to subjects I know nothing about, just to see people sharing niche expertise in plain language with one another. Sometimes it’ll be some veteran survivor of the pre-mobile internet where all the fonts are super small and you have to zoom in awkwardly on a phone to read any of it. I turn into the “sickos” meme instantly when I find something like that.

Thanks Jaime! Buy her music, support her on Patreon, read her column, and follow her on Twitter.

More My Internet here