The chronically online epidemic

We’re reaching a tipping point for internet discourse.

Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, from Kate Lindsay and Nick Catucci.

I’m freaking out a member of the CDC just called me and told me there’s a new pandemic on the loose. It’s called being chronically online, and one of the symptoms is subscribing to this newsletter. —Kate

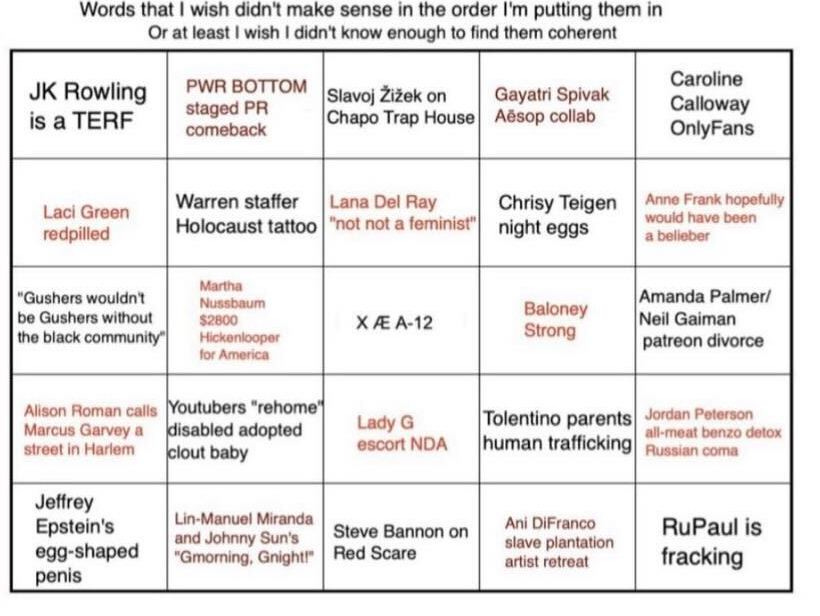

While the phrase “chronically online” (or “terminally online”) has been in the digital zeitgeist since the mid-2010s, the term has had a 2020s resurgence. Five or so years ago, being chronically online meant that, instead of leaving your house, the internet was your primary form of socialization. It was also your entertainment, in lieu of going to the movie theater or keeping up with TV. Maybe your job was on the internet, too. But in 2020, we all got chronically online, and now, the goalposts for being chronically online have shifted. As it turns out, though, people have had no trouble going that extra mile.

Recently, I’ve seen the term pop up on TikTok not just in the context of someone who spends a lot of time on the internet, but also someone whose reality is so warped by the social dynamics and discourse mechanics dictated by niche internet communities and other power users that their opinions and takes have become completely detached from the actual stakes of reality. (This isn’t to say that kind of chronically online person didn’t exist pre-2020, only that the affliction has become much more mainstream, especially now that one billion of us are bumping up against each other on the same app).

Someone who is chronically online in 2022 would tweet that advising writers to read books is ableist, or insist Anne Frank had white privilege, or make a list of problematic authors that puts Colleen Hoover next to William Shakespeare. Those are not random answers to a Mad Libs puzzle, but real arguments that have been made online in the past few months alone.

Put short, to be chronically online means contorting oneself in whatever way necessary to start a new round of internet discourse. You might be well-intentioned, but the point you're advancing can only be understood by people who already spend too much time online.

That said, there’s no objective definition of “chronically online.” And in fact, the term itself is frequently weaponized, used to invalidate the reasonable requests to think thoughtfully about how race, gender, sexuality, and other identities play into conversations on social media.

Still, the resurgence of the term signifies a growing exhaustion with the ever-accelerating, seemingly insatiable cycle of online discourse. The constant one-upping of takes and callouts has made Twitter—and now TikTok—genuinely unpleasant places to be. In the past couple weeks, using TikTok has drained me of any sense of peace or optimism about society. The benign outfit videos and homeware hauls I love are now just barely sprinkled between video after video of call-outs, hot takes, people fighting with commenters, and just overall bad vibes. Instead of talking like strangers who have just met, this environment has normalized approaching any kind of online conversation like the participants are already ten minutes into an intractable argument.

Why does this keep happening? As social media platforms collapse into one another and become overpopulated, users have to go to greater lengths to get noticed. Platforms like TikTok pick up on the flurry of reactions to an outlandish take and push the content in front of more people, who also react to it, causing what started as a niche internet drama to snowball bigger and bigger until, say, “womblands” comes to mean something to a majority of readers of a newsletter like this.

As long as algorithms and engagement incentivize this behavior, it’s not going to stop. But as our exhaustion grows, we may choose to stop playing our role in it. Step one is acknowledging when something is too chronically online to be worth engaging with. Step two? One day, with luck, a critical mass of people not acknowledging it at all.