The Millennial pause

And watching the internet move on without me.

Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, from Kate Lindsay and Nick Catucci.

Can you believe that, despite the pieces I’ve written about getting old on the internet and turning 30, I’m still in my 20s? —Kate

P.S.: Read the follow up to this piece, Hell hath no fury like a Millennial scorned.

There’s a TikTok video by creator @nisipisa that I haven’t been able to stop thinking about. It’s a stitch of Taylor Swift announcing the rerelease of Red in November.

“I am obsessed with the fact that not even Taylor Thee Swift is immune to the inevitable Millennial obligatory pause-before-you-start-talking-in-a-TikTok-to-make-sure-it’s-actually-recording,” Nisa says.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The “Millennial pause” hasn’t caught on as a thing, as far as I can tell, but it perfectly encapsulates part of the reason why the internet feels so weird to me right now: I no longer fully “get it.” The same way it’s too late for me to become fluent in a new language, I’ve passed the age when I can seamlessly adapt to the internet’s constant evolution. It requires a lot more work, and recently, I've felt like I’m watching the internet move on without me.

I now take so long to do basic tasks on my phone that my Zillennial sister yanks it out of my hand to do them herself. (Until now, I’ve been the one yanking the AppleTV remote away from my parents for the same reason.) I’ve started taking my selfies zoomed out at .5 because I read about it online. I just downloaded BeReal. These are all things I used to be on the forefront of, and am now sheepishly adopting far too late, hoping I don’t stick out the way it feels like I do when I post a TikTok or, say, go to Williamsburg.

“Cringe millennial” is now well-trodden territory in Gen Z discourse, and a lot of that caricature is based specifically on how Millennials act online. While Gen X and Boomers came at us for our IRL avocado toast and supposed IRL entitlement, Gen Z’s gripes are distinctly digital: the pauses, the zooming-into-our-faces-for-emphasis, the tweeting of “THIS” or “I did a thing,” or any given BuzzFeed headline.

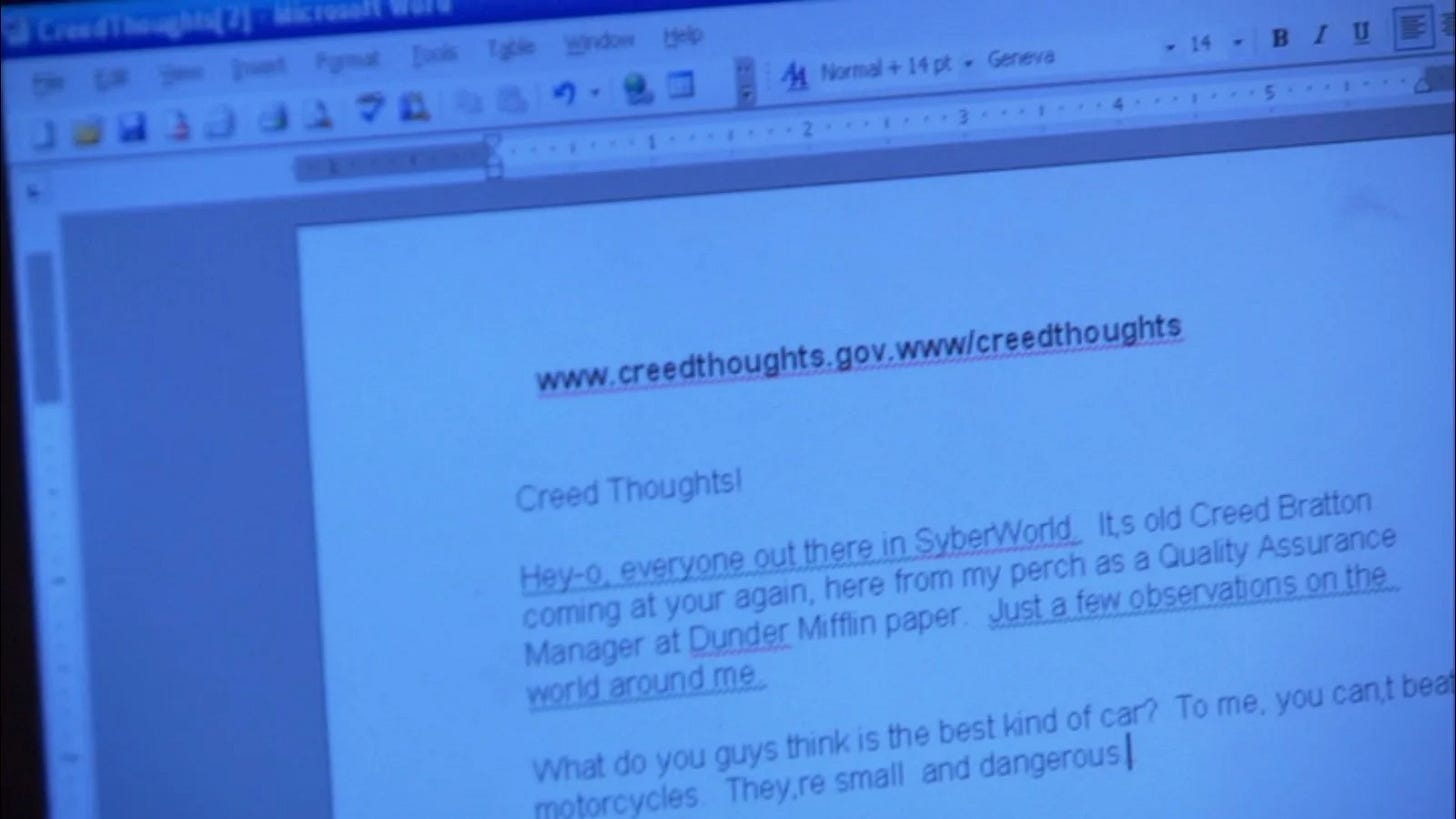

The betrayal I feel isn’t about being made fun of—partly because, I'm proud to say, I’ve never posted “THIS” in my life—but because it sucks to feel myself getting worse at the internet when, as far as I’m concerned, I was doing the internet first. Millennial behavior laid the groundwork for how we interact with each other online, but when I try to be an active participant in social media’s current iteration, I may as well be doing my own personal Creedthoughts. (Is referencing The Office in a post about Millennials a little too on the nose?)

This is something Charlie Warzel touched on last week in a conversation we had for Galaxy Brain:

I think that mid-to-late Millennials and very young Gen Xers are this weird straddle generation. Like, one of my earliest memories is playing with a working rotary phone my parents had in the kitchen of our house. But, also, I was online for the first time at like 7 or 8 and very much was raised online. But I walk around with this strange tortured awareness of like, It wasn’t always this way, and I’m often nostalgic for a thing that I don’t really actually remember but also sort of do.

The internet is different from other forms of culture because you can only be nostalgic for it in the abstract. I can watch movies from my childhood and listen to the music I danced to in college, but I can’t even find my old MySpace or message my friends on AIM. The internet, as I’ve written before, tends to disappear.

“I see a lot of much younger people engage with some of my writing about technology, and they’re like, ‘Stop overthinking it, man. We’re all just online. That’s life!’” Warzel said in our conversation. “And they are right, and I am overthinking it. But our experiences are different!”

I’m not nostalgic for a time before the internet. I'm nostalgic for the internet I actively defined, and there’s no playbook for being, essentially, a retiree in this new space. The only comfort is that Gen Z is living its own version of the internet that will, too, be inaccessible and unrecognizable in 20 years—or maybe, if Eugene Wei’s essay from last September holds true, it’s already on its way out.