Embedded is your essential guide to what’s good on the internet, from Kate Lindsay and Nick Catucci.🧩

This is why I shouldn't be participating in the metaverse. —Kate

When I spoke with Link In Bio’s Rachel Karten last week, we talked about the ways she disconnects from social media.

“I think of my big screen as being self-care,” she told me. “I'm like, ‘I'm just watching TV. That's not bad for me. I'm not looking at my phone.’ But it's still another screen, unfortunately.”

This piqued my attention, because earlier that week I had been catching up on vlogs from Michelle and Aline and heard Michelle Dufflocq say something similar about her mission to watch new TV shows.

“It gets me off my phone, which is great,” she says. “I’m literally just watching another screen, but it’s getting me off my phone.”

I, too, had noticed recently that there was something pleasantly retro about sitting down on my couch to watch the latest episode of a TV show, especially as more and more of them have started reverting back to weekly episode drops. But mostly, TV feels better for me than scrolling social media or falling into a TikTok k-hole. I’m engaging in the ancient human tradition of storytelling, I say to myself as Amanda Seyfried as Elizabeth Holmes dances to Lil Wayne’s “How To Love” on my screen. This is the legacy of my ancestors.

TikTok seems to be the best thing that’s ever happened to TV’s image. In 1990, The New York Times published a piece titled “How Viewers Grow Addicted To Television.” The writer profiles a 32-year-old police officer who has three TV sets in his home and a 33-year-old divorcee who says she watches television 69 hours a week (nice).

“Recent studies have found that 2 to 12 percent of viewers see themselves as addicted to television: they feel unhappy watching as much as they do, yet seem powerless to stop themselves,” the piece reads.

In the early 2000s, the term “binge-watching” came into use, and as recently as 2021, psychologists were studying the effects of it on mental health. Then, sometime between then and now, we hit our heads hard enough to forget all of that, and now categorize watching TV alongside other self-care activities like “reading a book” or “going for a walk.”

That’s not because those activities are suddenly all equally good for our health—everything that was reported about TV’s adverse affects on our brains presumably still holds true. What’s changed, I think, is that like reading a book or playing a sport outside, watching TV acts like a speculum (sorry) on our attention spans, which have been narrowed to 15 seconds by Reels and TikTok. The itch to check our phones and give in to the addiction is there, but watching the big tube is an effective tool for distracting us from the urge for as long as possible. We're so convinced that it’s in our best interest to reverse the effects of social media that even watching a 30-minute TV show uninterrupted seems constructive.

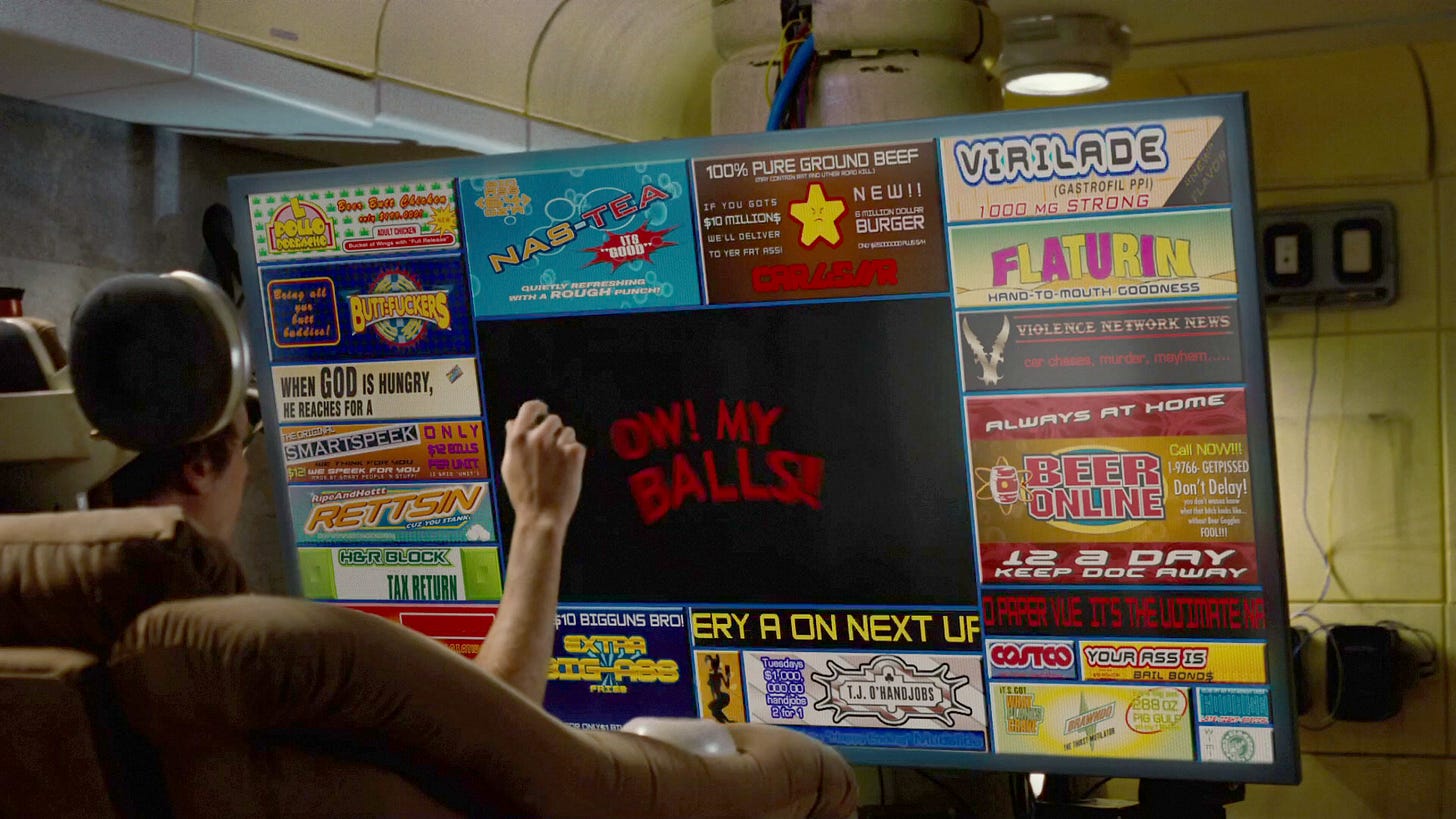

This isn’t meant to sound as pessimistic as it perhaps reads. I don’t think we’re approaching Idiocracy. I still read books and go on walks and see my friends and do normal, real-life things more than I’m ever on my phone. What freaks me out is how, 30 years from now, this piece might age as bizarrely as the one in The New York Times, and that by then, we may be using TikTok as a break from some even shorter, more addictive form of entertainment.